GIVE VISITORS A BREAK

I wasn’t taken to museums and galleries as a child. Apart from the times I was skipping lessons and sneaking into the Whitworth Art Gallery, I have one vague memory of a vast echoing hall somewhere with a huge skeleton suspended from the ceiling, but that’s it. We went to the zoo, the seaside, to parks and the circus at Christmas-time, but museums and galleries weren’t on our family outing radar. I really discovered museums and galleries as a university student and had to learn the ropes as an adult.

There are so many unwritten rules and rituals: do you have to walk round at a certain speed, visit rooms in a particular order? How close can you get, can you touch, are you allowed to speak? Is it OK to dislike a painting by a grand master? It took me years to accept that it wasn’t compulsory to read every bit of text or study every single artwork. I still feel a frisson of guilt if I go round a gallery the ‘wrong way’ or don’t stop and study every priceless object.

I reckon that the average adult attention span is roughly half an hour. After that, our minds begin to wander, backs start to ache and eyes glaze over, and the weird thing is that we often carry on, moving from work to work, room to room until we’ve 'done' the museum. Whatever the cause of this museumitis, I wonder whether we professionals could do more to recognise the affliction and encourage people to rest and rejuvenate themselves? Might boost sales in the café and shop! We could nudge visitors with motorway-style signs saying, "Tiredness kills enjoyment - take a break".

TERRIFIC TEENAGERS

An interview in the Guardian this week https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/aug/17/teens-get-a-bad-rap-the-neuroscientist-championing-moody-adolescents has got me thinking differently about young people and wondering how a more understanding approach might transform how museums engage with this much maligned demographic. I realised that ironically, like many ex-teenagers, I find the tribe exasperating at best and intimidating at worst. I have little patience with or sympathy for what often seems like lazy, capricious or self-destructive behaviour, despite, if I’m honest, having been that boy myself.

Neuroscientist, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore’s research suggests that there may well be a physiological explanation for what you might call ‘Kevin syndrome’ – referencing Harry Enfield’s hilarious (to adults) portrayal of a polite and helpful boy who morphs into a moody monster overnight as he turns 13.

Far from being wilful misbehaviour, Blakemore describes this metamorphosis as “a critical period of neurological change” which she claims explains and to some extent exonerates typical traits such as refusing to go to bed at ‘a reasonable hour’ and the inability to get up in the morning; obsessive self-absorption; inability to resist peer-pressure; reckless risk-taking, and a morbid FOMO (fear of missing out), all exacerbated, of course by the lure and power of social media.

It’s well known that teenagers are a ‘hard to reach’ audience, but maybe it’s us who are playing hard to get. If Blakemore is right, perhaps we should think more creatively about what time of day we run events, what kinds of programmes and facilities we offer young people, how we promote our offer and how we recruit participants. UCL Academy recently became the first British school to shift the start of the day to 10am in recognition that teenagers aren’t fully present until mid-morning. I agree with Blakemore – it’s time we gave teenagers a break.

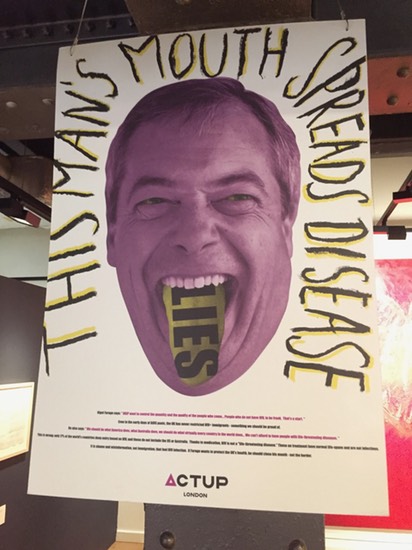

ASKING FOR TROUBLE?

Every decision we make in museums is potentially controversial: what to collect and how we acquire it; where and how objects and specimens are stored; how they are used and by whom, if we decide to dispose of collections and how that is done. Depending on their background, upbringing, education, training and professional experience, staff will have a range of opinions on these issues and will make them known one way or another. And visitors or users carry with them a similarly broad range of expectations and prejudices, which is why feedback should be treated with caution and careful consideration.

Of course it is important to listen and learn from audience research, but this vital intelligence needs to be processed through the filter of our professional knowledge and expertise. We need to trust our own experience, scholarship and instinct, and value our creativity.

An exhibition or display with something to say is likely to shock, outrage or upset somebody – it’s a cliché but it’s true: you can’t please all the people all the time. What we don’t want is for people to be bored or disengaged. Museums should be places of passion and stimulation, where visitors discover new things about themselves and the world around them.

If you accept the challenge to embrace controversy, the process needs to be carefully managed internally and externally. Communication is the key. You need to be clear about why you are presenting what people see and experience. How did you make your decisions? You must be prepared to explain the philosophy, rationale and purpose behind the approach and make sure you’ve thought it through. Accept that some people will react against what you do and be ready to respond to criticism with confidence and solidarity.

TIME TO REFLECT

The theme of this year’s GEM conference (Adapt & Thrive: Weathering the impact of change on cultural learning) was a challenge to consider and confront the reality facing our sector – increasing pressure to perform coupled with ever-dwindling resources. The only sensible response according to two of the keynote speakers, Bob Janes and Piotr Bienkowski, is collaboration with the communities our institutions are part of. In fact, they maintain that it is the only way that museums will survive in the future.

In his keynote address, Piotr shared a frank and bleakly comic account of his experience as Director of Paul Hamlyn Foundation’s experimental programme – Our Museum: Communities and museums as active partners. In his talk: Why change fails – and what YOU can do about it, Piotr stressed that organisational change is not a project; it is an ongoing process of reflective practice in the same way that CPD involves continuous learning on a personal level.

A common response to calls for reflection is that we are too busy: we don’t have time for ’naval-gazing’, but reflective practice is the opposite of indulgent introspection – it focuses on action and improvement. Without regular and thoughtful consideration of how we are doing and what we could do better, we are likely to repeat the same mistakes . Collaboration means give and take, redistributing power and influence, and a willingness to compromise and change. Some would argue that reflective practice steals time from the day job – Bernadette Lynch, whose incisive report Whose cake is it anyway? was the inspiration for the Our Museum programme, says: reflective practice IS the day job!

QUIET PLEA

Although I really enjoyed the GEM (Group for the Education in Museums) conference 2016 in Edinburgh, after two days of constant interaction I was ready for some recovery time. As a self-identified 'professional extrovert’, I’m acutely aware of the need to recharge my batteries on a solitary walk or with my nose in a good novel. I also know how difficult it is for people like me at the “I” end of the E-I spectrum to come up with a snappy question or response to a keynote speaker or workshop leader, especially in front of a large audience. We feel the need to digest and reflect before responding, especially to such probing and serious questions!

A few years ago, when I watched Susan Cain's TED talk just after she'd published Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking I thought: Wow, that's me! I was reminded of the first time I visited my girlfriend's family. I grew up in a house with very few books, where it was seen as rude to read in front of other people so I was amazed to see her family sitting around companionably absorbed in their chosen texts, occasionally exchanging comments or getting up to make tea or coffee. It was a revelation for me – it really felt like coming home, but it took me years to recognise this as introversion and not to feel guilty about it. I only recently realised that introversion is the main reason why I'm so rubbish at social media – my default thought is "Why would anyone else be interested in what I have to say?" I think Cain is absolutely spot on in her assessment that the 'developed world' in the 21st century is biased in favour of the extrovert to the detriment of society as a whole and that this needs rebalancing.

In recent years, museums and galleries have become noisier, which, in many ways and especially for people who find silence oppressive, is a good thing. Excited children feel freer to express their wonder, while a background soundtrack helps socialites mingle. However, (and you knew that was coming, didn’t you) there must still be a place for peace in our full-on world: in our public spaces, programmes and workplaces. The GEM Foundation Course – now in its second year – aims to foster a balance between interaction and contemplation, debate and deliberation, offering participants the knowledge and skills to create learning environments that cater for all learning styles and personality types, from life and soul to contented bookworm. Not all quiet on the museum front, just enough.

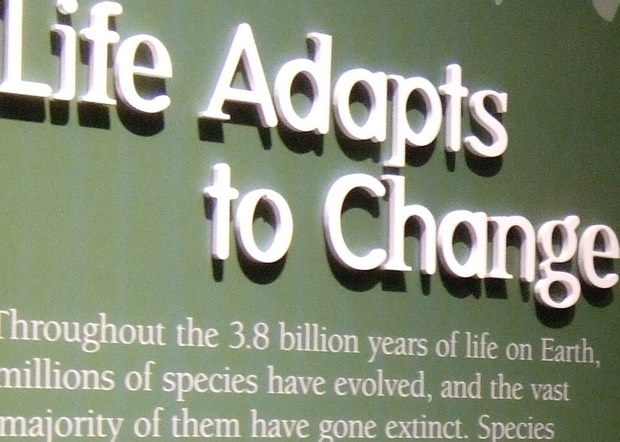

ALL CHANGE!

For me, one key thread running through the GEM (Group for the Education in Museums) conference 2016 was the idea of ‘agency’: taking steps to tackle change individually and collectively; encouraging our colleagues and organisations to recognise new realities and roles, and sharing spaces, resources and political power with users to enable our audiences to participate actively as equal partners.

Piotr Bienkowski stressed the importance of champions of change, people who create a critical mass of positive energy that can move mountains. I’ve heard this described as a "coalition of the willing" and seen the difference that positive peer pressure can make. Robert Janes challenged us to get off the fence, ditch ‘neutrality’ and take a stand on big issues such as social and economic inequality, runaway consumption and climate change. Bob’s keynote asserted that museums, because of their unique position as custodians of our planet’s history and unequalled levels of public trust, have a responsibility to lead the debate and search for solutions.

Change can feel scary and overwhelming. We can choose to deny it, run away from it or engage with it, but change is inevitable and unavoidable, as Ruth Gill memorably illustrated by reminding us that – on a cellular level – she was transforming before our eyes. The question is how are we going to respond now that conference is over? How can we apply what we’ve learned in our jobs, our organisations and networks? How can GEM play a role as an agent of change?

ON THE EDGE

We museum and gallery educators often complain about the peripheral place of learning in our institutions and bemoan the bolt-on approach, especially when funding cuts begin to bite, but in recent years our work has gained in prominence and influence, with educators involved at all levels in planning, policy making and operational activity. I’m one of a growing number of people who has had positions in senior management but I’m starting to wonder (at the risk of shooting myself in the foot) whether ‘museum central’ is the best place for learning to live.

I recently came across a really useful edition of a U.S. publication – the Journal of Museum Education – that was dedicated to Institution-wide Interpretive Planning. In an article about the educator’s role in “transformation and interpretation” Czajkowski and Hill acknowledge that learning is often physically and psychologically isolated from what is traditionally defined as the core function of a museum, but they question the desire to move education in from the periphery. They point out that the margin is where change happens: it’s the place where audiences and objects interact. Educators understand the museum from outside in, and are ideally placed to act as agents of transformation, mediating negotiations between individuals and institutions.

In support of their proposition, Czajkowski and Hill cite the work of author and social activist, bell hooks (no that’s not a typo – she doesn’t capitalize her name). Applying locative politics, hooks argues that the margin is the strongest position from which to “challenge dominance and deconstruct hierarchical power”. This reminded me of the old saying that you should be careful what you wish for. If we embed museum learning in the establishment do we risk losing something much more valuable? Perhaps, instead of striving to belong, we should celebrate life on the edge.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ‘AND'

We struggle for reconciliation in many areas of our work: conservation or access, objects or ideas, traditional or avant-garde. When it comes to interpretation in art galleries, the binary position seems to be either ‘experience’ or ‘interpretation’, as though the purity of the former is tainted by the latter, as though intellectual understanding cancels out the aesthetic or emotional in the equation of art appreciation. If this were true, then art experts, having lost their innocence, would be unable to enjoy the works they curate.

The truth is that experts don’t feel any lack in a minimalist gallery because they carry the interpretation with them in their heads. For the rest of us, context can add hugely to the pleasure of art and can reassure people who feel unsure of gallery etiquette. Understanding who made a work of art, how it was made, why and when can help us make sense of the piece and move us beyond “Do I like it or not?” I for one can still be moved and inspired by works that I studied at university.

The first chapter of Elaine Heumann Gurian’s excellent 2007 book Civilizing the Museum is called The Importance of “And”. In the book she challenges us to welcome and balance difference rather than seeking to oppose what we perceive as the threatening other. I think it’s time we stopped wasting energy setting up false distinctions and worked together for the benefit of all our audiences. We could start by replacing “or” with ”and”.

THE THING’S THE THING

Objects, the things we make, acquire and consume and the memories or associations they trigger, are often the means by which we construct our life stories. Objects aren’t ‘containers of truth’, they are catalysts for personal engagement and understanding. That is not to say that there aren’t facts or information about objects that we can pass on, it’s more to do with an acknowledgment that there are many ways of interpreting collections and that we shouldn’t privilege one over the others.

Some people say that objects speak for themselves and need no interpretive intervention from us. In a sense, I think that’s true because every visitor, whether Art History professor or 5 year-old child, will make sense of the object in her or his own way if they are given direct, unmediated contact, but the understanding they arrive at will not necessarily be the ‘correct’ one. The question is: do we want to offer people a particular interpretation at certain times and in specific circumstances? If we explain clearly that this is a view of the object from a certain perspective rather than the one true interpretation, then we can enter into an interesting dialogue with visitors.

I think there are two keys that can help to facilitate engagement and understanding. The first is to do with experiencing familiar things in unfamiliar ways. Feeling that we “know” a museum or gallery collection, as we are expected to, can get in the way of this process, but our visitors can free us up by showing us the objects through their new eyes. The second key is about prolonging the encounter with the object to enable deep reflection and response to it. This leads to what many people are now calling ‘individual meaning making’.

As Viktor Shklovsky says in Art as Technique, “The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects “unfamiliar”, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object: the object itself is not important…